Nearly everything today is written with an audience in mind. We aren’t writing to express ourselves; we’re writing to be seen.

I am currently reading a book by David M. Rubenstein called The American Story. Back in 2013, philanthropist Rubenstein started something called The Congressional Dialogue series. This event saw members of Congress from both sides of the aisle gather for dinner and listen to Rubenstein interview a master historian about their books on such illustrious figures as Washington, Lincoln, and Adams—the usual suspects. He then turned these lectures and interviews into books.

I love history; it’s where we see our past and our future played out simultaneously. It’s where we meet men and women who did incredible things, moving people in ways that inspire awe. I particularly enjoy it when these master historians talk about the letters our Founding Fathers wrote.

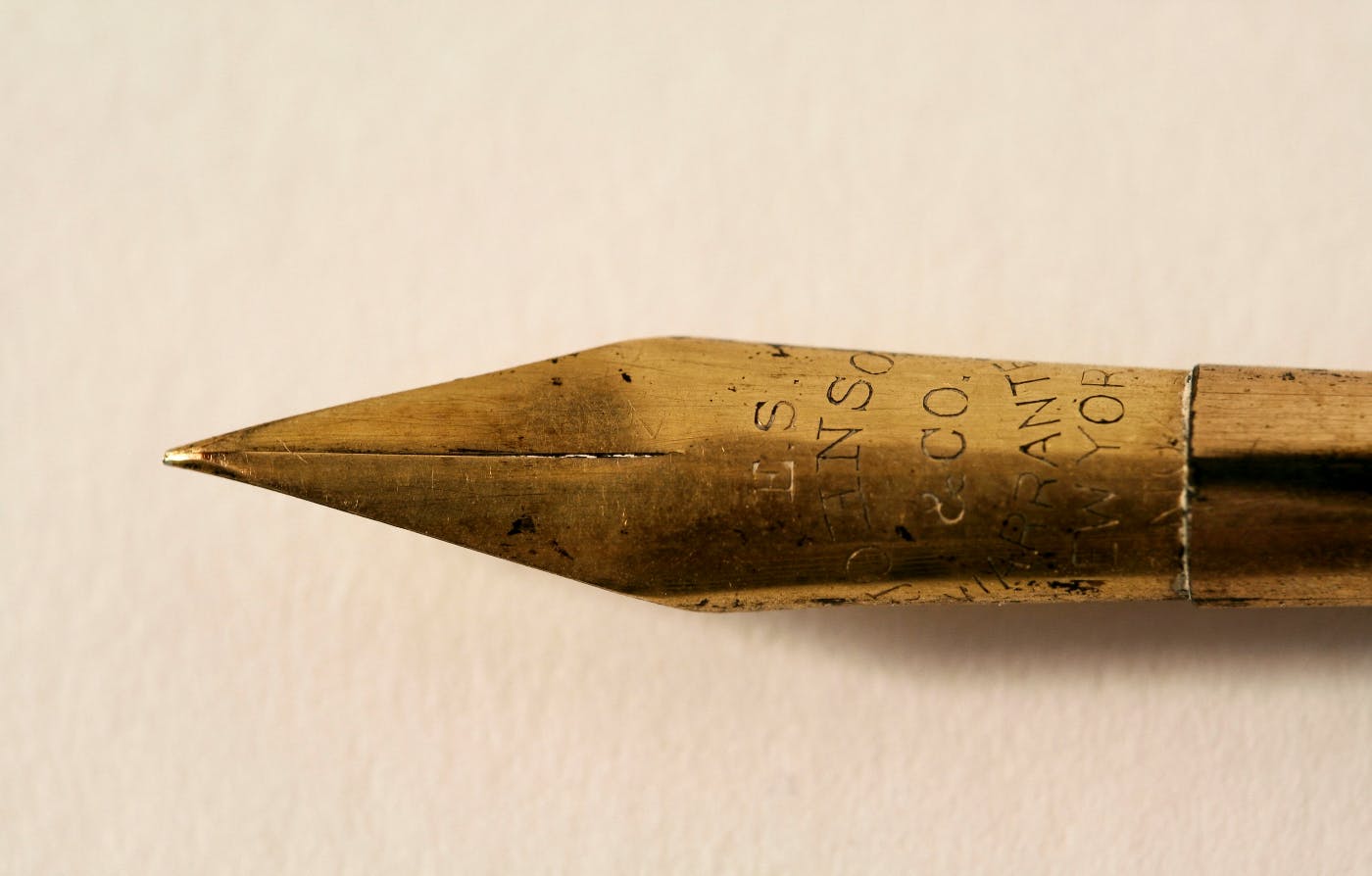

What I’ve noticed, and what has been highlighted, is the difference between the letters written by our Founding Fathers and those written by our Founding Mothers. John Adams and his wife exchanged 1,100 letters, many of which we still have. They reveal a very different side of Adams than most history books recount—personal, full of descriptions about where he is and what he’s doing. Their letters also reveal the depth of passion and understanding between the two. Even when John was in London, and letters took weeks to reach each other, the relationship came through clearly as day.

These letters are incredible for their content and style, allowing us to view history authentically. Today, these letters are a significant part of how we understand how this country came to be. But at the time, they were just letters. Without the internet or cell phones, people wrote daily about everything. Honesty and simplicity were baked in because the writers didn’t think they would have a worldwide audience. They wrote to family and friends about day-to-day life. The key here is that they were not writing for an audience.

The Difference Between Writing Then and Now

This contrast between past and present is striking. Our modern form of writing—whether it be on blogs, social media, or even emails—is vastly different. Nearly everything today is written with an audience in mind. We aren’t writing to express ourselves; we’re writing to be seen. And when you’re focused on being seen, something important is lost: truth.

Our Founding Fathers, particularly in their personal letters, were writing from the heart. They didn’t have the pressure of public opinion breathing down their necks. The same can be said for the Founding Mothers. Their letters, too, carried the weight of daily life—often filled with discussions about the home, children, and community. They wrote about their world, unfiltered and unapologetically real.

Now, look at modern writing. So much of it feels curated. Blogs and social media posts are polished, over-edited, and crafted to gain likes, shares, and positive feedback. When we write for others, when we’re conscious of how our words will be received, we lose a sense of realness. In essence, we stop feeling our writing.

The Dangers of Writing for an Audience

Writing for an audience isn’t inherently bad. But when every sentence, paragraph, or post is tailored to please, impress, or entertain, it stops being a reflection of the writer and becomes a performance. This performative nature changes the way we express ourselves. Rather than digging deep into what we really feel or think, we focus on how it will be perceived.

For instance, the need to go viral or become a social media influencer influences how many people approach their online content. The authenticity that could lead to genuine connections is sacrificed in favor of appearing polished or popular. How often do we find ourselves overthinking a post, refining it again and again so that it sounds just right or will appeal to a specific audience? That constant self-editing is exhausting, but more than that, it’s dishonest. And it affects not just our communication but how history will eventually record our time.

If we consider letters like those between John and Abigail Adams, they provide us with an intimate look at their lives and the early days of the United States. But imagine if they’d written those letters with a public audience in mind, adjusting their language and message to suit potential readers. Would we see the same personal and passionate John Adams we know today? Likely not. It’s the honesty, the lack of self-consciousness, that makes those letters so valuable.

Why Authenticity Matters

Authenticity in writing allows us to connect with others on a deeper level. When we strip away the need to be approved or validated by an audience, our words become more meaningful. We start to see the world and ourselves more clearly. Writing truthfully also has a larger implication: how we shape history.

As individuals, we are constantly contributing to the record of our time. What we write and how we express ourselves will one day become part of the historical fabric. If everything we produce is filtered through the lens of audience perception, what kind of legacy are we leaving behind? How will future generations interpret the reality of our lives if we only show them the curated version?

The letters of the Founding Mothers are invaluable because they reflect real, everyday life in their time. Their honesty gives us a sense of what life was like beyond the famous events and historical milestones. But in today’s digital world, that kind of unfiltered communication is fading.

Practical Ways to Write Truthfully

So, how can we reclaim authenticity in writing and stop writing solely for an audience? Here are a few practical steps to help you start writing truthfully:

- Write for One Person: Whether it’s a journal entry or a letter, pretend you’re writing to just one person—maybe a friend or a family member. Forget about the broader audience. When you’re writing to someone specific, it helps your words flow naturally.

- Embrace Imperfection: Don’t worry about every sentence being perfect. In fact, it’s often in the imperfections that we find truth. If you over-polish your writing, you might end up scrubbing out the parts that make it real.

- Avoid Overthinking: Let the words flow. Sometimes, the most honest things we say come out in the moment. Don’t spend too much time thinking about how your writing will be received—just focus on saying what’s real.

- Focus on Experience, Not Performance: Write about what you know and what you’ve experienced. It's easy to get caught up in writing for approval, but that’s not where the value lies. The value lies in sharing the truth of your experiences, even when they’re vulnerable.

Writing Truthfully in Personal and Professional Life

Writing truthfully isn’t just for personal correspondence. It’s something that can be applied to all aspects of your life, including your professional work. When you focus on authenticity, you’ll find that people respond to it. Whether you’re writing an email, a presentation, or a blog, your readers will appreciate the honesty.

In business, truthful writing builds trust. Clients and colleagues respect you more when you’re straightforward and real. Just as the letters of the Founding Mothers give us a candid view of history, writing truthfully today can offer an honest reflection of who you are and what you stand for.

Summing Up

Our modern world may be geared toward writing for an audience, but there’s value in writing for yourself—or for no one at all. By reclaiming authenticity in our writing, we not only improve our communication skills but also create a more honest record of our time.

So, take a step back from the curated, polished writing you’re used to. Write for one person. Write without an audience in mind. You might find that, in doing so, you’ll start to see the world—and yourself—more clearly.

And who knows? Perhaps one day, your letters and writings will be authentic historical records that future generations will turn to when they want to know what life was really like in your time.